"No One is Above The Law": Donald Trump and the Myth of Justice

Some of America's most cherished myths are being summarily and necessarily destroyed.

DISPATCHES FROM A COLLAPSING STATE depends on your support. Subscribe now to support Jared Yates Sexton’s work and access additional materials, including exclusive posts, podcasts, videos, and Q&A’s where you get to ask Jared your questions.

For all of the damage Donald Trump has done, sometimes it’s necessary to appreciate the public services he has performed.

By ascending to the office of President of the United States, he exposed the shoddiness of our systems and the pervasive ugliness of our culture.

In constructing his MAGA Movement, he made visible the authoritarian elements that course just under the skin of the American body politic.

With his unmatched and staggering incompetence - having been one of the worst performing “businessmen” in the country’s history - and his persistence in remaining rich, powerful, and influential, he did us the favor of exposing just how farcical the notion of a “meritocracy” really was.

And now, as we watch the legal system contort itself and sweat and struggle to explain its inability to hold him accountable, we are witnessing the demise of yet another American fairytale.

It was only a few weeks ago that Attorney General Merrick Garland made headlines by claiming that “no one is above the law” in an impromptu discussion with the press. Garland, at the time, was addressing Trump’s role in fomenting an attempted coup on January 6th, 2021 and in pushing for the overturning of the 2020 Presidential Election. That feels like years ago and is, headshakingly enough, only one of several legal controversies that have plagued Trump this summer.

Now, on the heels of the infamous search of Mar-a-Lago and the discovery of top-secret documents, the myth of a fair and impartial legal system is being destroyed in broad daylight for everyone to see.

That notion is and has always been absurd. People of color and vulnerable populations have known for generations that our legal system is, at best, prejudiced to its core, but the crash course that Trump is providing its remaining defenders is literally priceless. For all of the talk of “the walls closing in” and “this is the thing that gets him,” even this delay in arresting and prosecuting him after he has been caught dead-to-rights stealing state secrets (whether it was out of shoddiness, vanity, or in the pursuit of treasonous profit) exposes how undeniably biased all of this truly is.

The idea that you or I could even stand in a room with these materials is absurd, but if we somehow or another managed to pilfer so much as a page of them without getting shot or slammed to the ground and took one step in the direction of the door our fates would be sealed. And yet, even if Trump is held accountable, which remains to be seen, such a gigantic step would have to wait until after November’s midterm elections.

Good luck avoiding prosecution as to not influence a political contest or, god forbid, avoid inspiring riots in the streets.

In this, like all things, Trump has served as a Rosetta Stone that reveals the biases that are written into our laws and codes and systems intentionally to privilege an economic elite. Wealthy men like Trump are allowed to oversee the restless redistribution of wealth from the bottom up, poison our air and water and food, wreck our environment, navigate the legal and tax codes like a gnat gliding through a net, and trade billions in ill-gotten profits for a few hundred thousand dollars in fines, but a regular person passing a counterfeit $20 bill is wrestled to the ground and killed in cold blood.

It is Trump’s laughable incompetence and slate of obvious crimes that allows the illusion to be troubled. Most of the wealthy and powerful’s transgressions are hidden behind jargon and only decipherable by experts. They exist as so much ephemera passing through the air. As is the case in all things Trump, these crimes are absurdly self-evident. They are taunts. Dares for the system to do something, anything.

This passion play we are witnessing is frustrating. Infuriating, even. The hypocrisy is painful. But, in a way, we should be grateful. The powerful would so much rather this inequality hum beneath a veneer of equality and impartialness. The stability of the system requires this illusion and, when it is troubled, the possibility for change arises and can thankfully become a reality.

What we are dealing with here is a moment rife with possibility. Because when we realize exactly how these things function, how obviously they are corrupted and corruptible, what also becomes obvious is the need for reform and progress.

THE MIDNIGHT KINGDOM: A HISTORY OF POWER, PARANOIA, AND THE COMING CRISIS is Jared Yates Sexton’s new book and the story of how we have arrived at this dangerous moment. This book details how white supremacist lies, Christian myths, and a culture of greed and exploitation created our modern world on behalf of the wealthy and powerful and now threatens to plunge us into an authoritarian nightmare of a future. There’s still time to escape this fate, but all depends on our ability to learn from the past

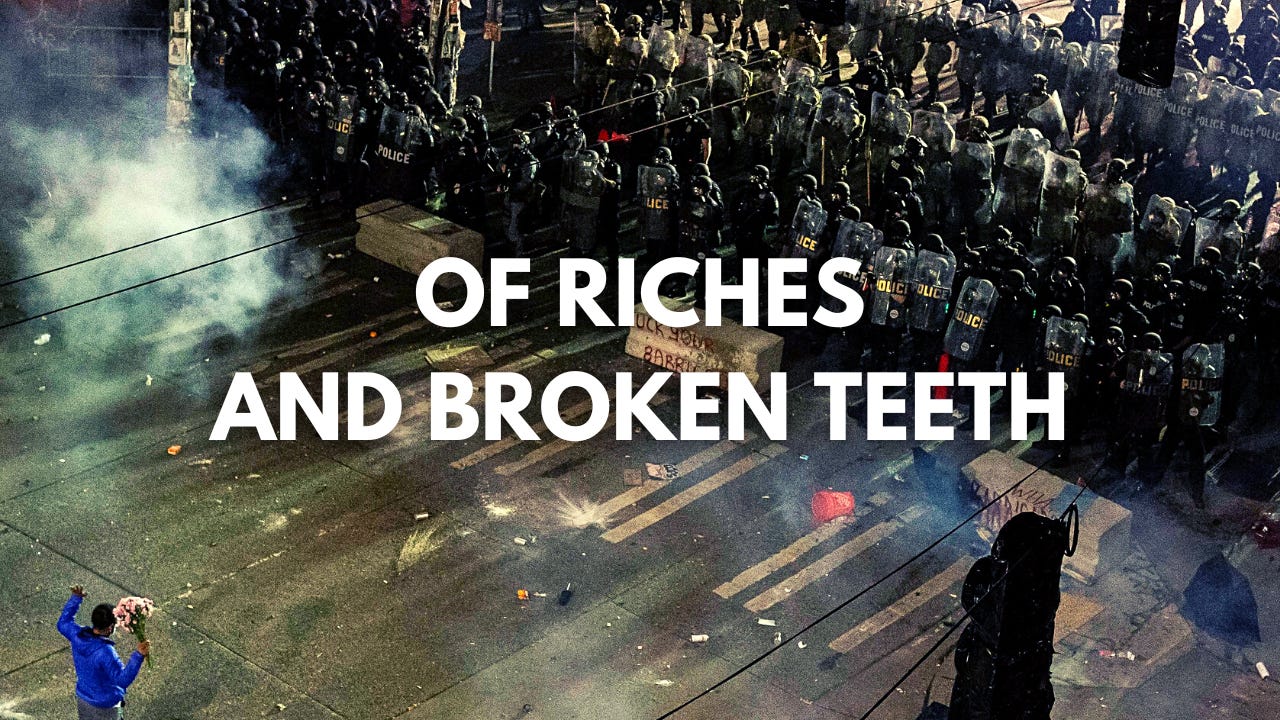

In Ancient Rome, they were called the Humiliores and the Honestiores.

The former were common people. Their lives fraught with toil and struggle. At any moment, their existences might be upended and their bodies violated. One contemporary writer described their day-to-day experience as one of “broken teeth,” citing the propensity of guards and thugs in the employ of the wealthy to visit upon them extreme violence.

Standing atop the hierarchy were the Honestiores, the nobility that enjoyed the empire’s many splendors. What was stolen from “barbarians” outside the demarcations and the Humiliores alike was theirs to accumulate and indulge. The expansion of the empire, in a foreshadowing of what would come with the United States, was done for their benefit and at their behest. Their wealth was a signifier of their political power, which manifested within the halls of government, where they reigned.

In this stratified environment there was no doubt as to what the law was and how it served the status quo. The Honestiores were above the brutality. Humiliores were its targets and subjects.

Though the United States and other nations of the liberal era prefer to present themselves as enjoying impartial legal systems, the purpose has always been the same. Capitalism and liberalism meant to strip the religious underpinnings of Christian orthodoxy and hereditary titles from the public sphere, but the inequalities were never meant to be troubled. Instead, the “neutral” nature of these ideas hid those inequalities under the veneer of impartiality. But the wealth and power accrued from colonialism and human slavery were laundered and replicated, pushed forward into a “new start” where the beneficiaries could claim they had “earned” their fortunes.

An added feature to this system was the lie of the meritocracy, or that those who suffered were less victims of prejudice or circumstance and, instead, failures who deserved their lot in life. Liberalism’s emphasis on protection of “property,” including its minoritarian system (read: republicanism, “checks and balances,” the construction of our governing bodies), further privileged the privileged, reasoning that their wealth and power meant they were the only people worth trusting with more wealth and more power.

So, you arrive at a self-replicating system where old concepts such as the Humiliores and Honestiores continue to perpetuate, but are veiled behind the illusion of fairness. Justice is “blind” until it isn’t. The ability to hire firms full of high-priced lawyers is a manifestation of the privileges afforded by wealth. Corporations stock themselves with experts whose entire job is to not only know the law backwards and forwards but to intimately understand its loopholes. Often because they either authored them themselves or lobbied for their placement.

Infractions by the Honestiores are treated gingerly. At worst, they result in brief sojourns to cozy “prisons.” Mostly, they’re overlooked or handled with polite slaps on the wrist that inform the offenders where the line will be drawn moving forward.

Meanwhile, small and petty crimes by the Humiliores must be met with overwhelming force because the law is there to protect the property of the wealthy. Since the beginning of the nation state, law enforcement has been a means of keeping the masses in line for just that purpose, acting as an occupying force at war with its own population.

The awesome and absurd nature of Trump’s crimes lays this bare, but also exposes how the myth of the nation state functions as a unifying force and gravity that holds this all in place. Nuclear secrets and intelligence are the crown jewels of the state, but deep down the very ideas of “treason” and “patriotism” have always been cudgels meant to inspire fear and deference while the state itself served to hold the structure together. The wealthy and powerful, all the while, used their understanding of these fictions to operate free of the gravity and fear.

Those nuclear secrets and intelligence, after all, are there to assist the state in overseeing the accumulation of wealth by the wealthy. In essence, they belong to the wealthy and are, more or less, theirs to oversee.

Again, the crumbling of these myths is demoralizing but also empowering. The illusions are meant to maintain faith in the status quo and our systems. They’re there to stave off dissatisfaction transforming into dissent, organizing, and democratic actions. But as the system grows more and more aggressively cruel, as the accumulation turns to austerity, and as conditions grow intolerable, there is more incentive to take chances. To trouble the state of things.

And, in the end, waiting on this decrepit and unfair system to effectively answer the threat it has created and nurtured turns to a desire for change. It makes a necessary reckoning all the more possible. Because with this level of corruption it’s not even a question anymore whether it might be time to try something else.

Jared, thank you. This post is so good that I literally cried. And I subscribed. I'm not sure for how long because I'm struggling with some bills right now, but you deserve as much support as possible. People need to read your work. I'm seeing so many people still in denial, believing that Trump is the beginning and the end of the crisis in our country, and they don't understand that what is happening now was only a matter of time. All it takes is a lot of anger, a dose of grievance politics, and a demagogue like Trump, who has convinced millions of people that he, a privileged white knuckle-dragger, is "fighting for you." History repeats itself.

“What we are dealing with here is a moment rife with possibility. Because when we realize exactly how these things function, how obviously they are corrupted and corruptible, what also becomes obvious is the need for reform and progress. . . . Because with this level of corruption it’s not even a question anymore whether it might be time to try something else.”

Over a half century ago, 19 years old, ‘Summer of Love’, 1967, I stood on the back stoop of a third-floor walk-up in Old Town, Chicago, gazing at the early dawn glistening around the towers of the Loop thinking, “Social reality is a construct and, as such, it can be deconstructed and reconstructed to manifest whatever social reality we want. Which begs the question, what social reality *do* we want? Apparently, it isn’t the one we currently occupy. Which begs even more questions such as, ‘Whose social reality *is this* anyway?’” That I was also coming down from a 250µ dose of Purple Owsley no doubt significantly influenced this insightful train of thought.

What I’ve learned since then is that the problem isn’t what we think it is. It isn’t *what* we think — but *how* we think.

Less than three years after that early morning revelation, one of the authentic geniuses of the previous millennium, Gregory Bateson, put it this way:

“Freudian psychology expanded the concept of mind inwards to include the whole communication system within the body—the automatic, the habitual, and the vast range of unconscious process. What I am saying expands mind outwards. And both of these changes reduce the scope of the conscious self. A certain humility becomes appropriate, tempered by the dignity or joy of being part of something much bigger. A part—if you will—of God.

“If you put God outside and set him vis-à-vis his creation and if you have the idea that you are created in his image, you will logically and naturally see yourself as outside and against the things around you. And as you arrogate all mind to yourself, you will see the world around you as mindless and therefore not entitled to moral or ethical consideration. The environment will seem to be yours to exploit. Your survival unit will be you and your folks or conspecifics against the environment of other social units, other races and the brutes and vegetables.

“If this is your estimate of your relation to nature *and you have an advanced technology,* your likelihood of survival will be that of a snowball in hell. You will die either of the toxic by-products of your own hate, or, simply, of over-population and overgrazing. The raw materials of the world are finite.

“If I am right, the whole of our thinking about what we are and what other people are has got to be restructured. This is not funny, and I do not know how long we have to do it in. If we continue to operate on the premises that were fashionable in the pre-cybernetic era, and which were especially underlined and strengthened during the Industrial Revolution, which seemed to validate the Darwinian unit of survival, we may have twenty or thirty years before the logical *reductio ad absurdum* of our old positions destroy us. Nobody knows how long we have, under the present system, before some disaster strikes us, more serious than the destruction of any group of nations. The most important task today is, perhaps, to learn to think in the new way. Let me say that *I* don’t know how to think that way. Intellectually, I can stand here and I can give you a reasoned exposition of this matter; but if I am cutting down a tree, I still think “Gregory Bateson” is cutting down the tree. *I* am cutting down the tree. “Myself” is to me still an excessively concrete object, different from the rest of what I have been calling “mind.”

“The step to realizing—to making habitual—the other way of thinking so that one naturally thinks that way when one reaches out for a glass of water or cuts down a tree—that step is not an easy one.

“And, quite seriously, I suggest to you that we should trust no policy decisions which emanate from persons who do not yet have that habit.” *

And so, now, a half century later, here we are — twenty years beyond where Bateson easily predicted we would be: Perpetually on the eve of self-destruction. Who among us has learned to “think in the new way?” Who among us even has a glimmer of understanding about what this new way of thinking is?

Your analysis, Jared, is accurate so far as it goes — which isn’t nearly far enough. That is because what is failing is not merely the State but the entire foundation of Western thought from which it historically emerged and out of which we constructed it. You speak of troubling the state of things as if this ‘state of things’ exists independent of yourself; as if troubling “it” would be no trouble to you at all.

Yet we are all troubled one way and another, aren’t we? Increasingly so, too, in recent years — with no end in sight. The political demystification you write so eloquently about scratches the surface of an itch that plaques all of us. Unfortunately, scratching will not rid us of this plaque. Only revelation and subsequent transformation — learning to think in the new way — can do that.

* Excerpt from:

“Form, Substance, and Difference,” published in Gregory Bateson’s, “Steps to an Ecology of Mind,” 1972, Chandler Publishing Co.; Ballantine Books, Random House, New York.

“Form, Substance, and Difference,” was the Nineteenth Annual Korzybski Memorial Lecture, delivered January 9, 1970, under the auspices of the Institute of General Semantics. Reprinted from the General Semantics Bulletin, No. 37, 1970, with permission of the Institute of General Semantics.